Barbecue may be the unofficial mascot of the Fourth of July, but its roots tell a very different story — one soaked in smoke, survival, resistance, and yes… ribs.

Let’s Talk BBQ: It Didn’t Start with a Bald Eagle and a Red Solo Cup

Every year, like a perfectly timed tradition, the scent of smoked ribs, charred corn, and somebody’s questionable potato salad starts wafting through American neighborhoods as the Fourth of July rolls in. But while you’re dodging fireworks and refilling your solo cup, it’s worth asking: Why is barbecue the thing we eat to celebrate “freedom”?

The answer, like that overly charred hot dog your cousin insists on eating, is a little burned, a little complex — and completely misunderstood.

So, let’s tear the foil off the myth and get into the actual origin story of barbecue in America: where it really started, who really mastered it, and why that story doesn’t show up in your typical history books (or your dad’s grill-off playlist).

Spoiler: Barbecue Didn’t Come from George Washington’s Backyard Cookout

Barbecue is often painted with broad, patriotic brushstrokes — you know the kind: founding fathers roasting pigs while writing freedom songs in powdered wigs. Cute story. Not even remotely true.

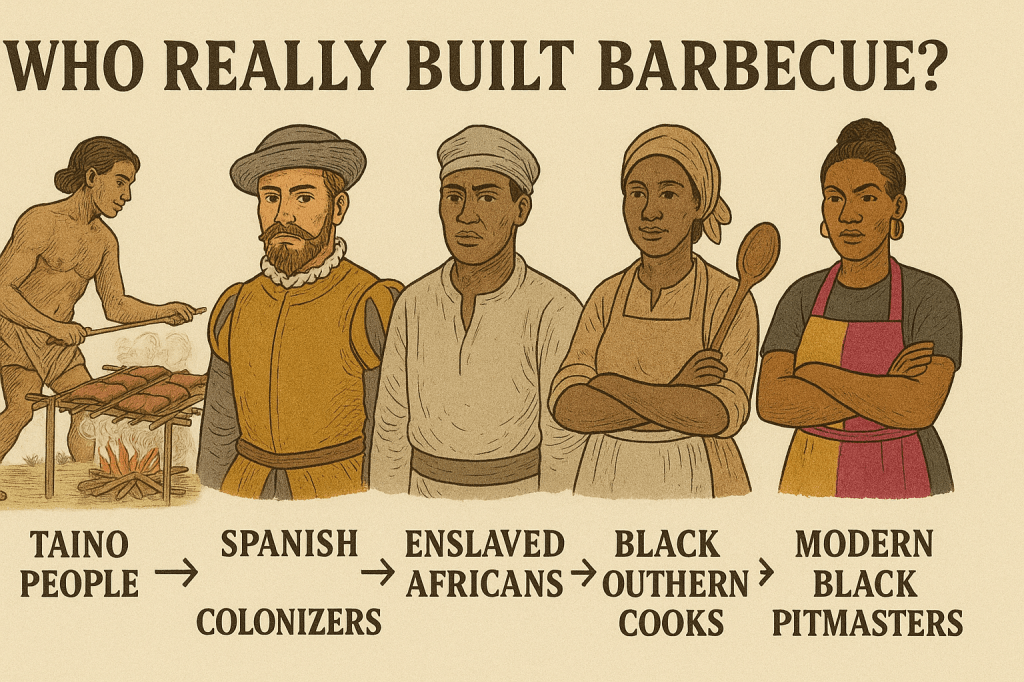

The real roots of American barbecue trace back to the Caribbean — and even deeper, to the Indigenous and West African cooking traditions that enslaved people brought with them or learned to adapt for survival.

According to food historians (and backed by this NPR breakdown), the term “barbecue” comes from the Taino word “barbacoa,” which described a wooden rack used to cook meat slowly over fire. Spanish colonizers latched onto it and spread it, and eventually it landed in what’s now the American South — where plantation owners took the credit while enslaved Africans did the actual work.

Enslaved Cooks Built the Barbecue Empire — Without Ever Getting a Crown

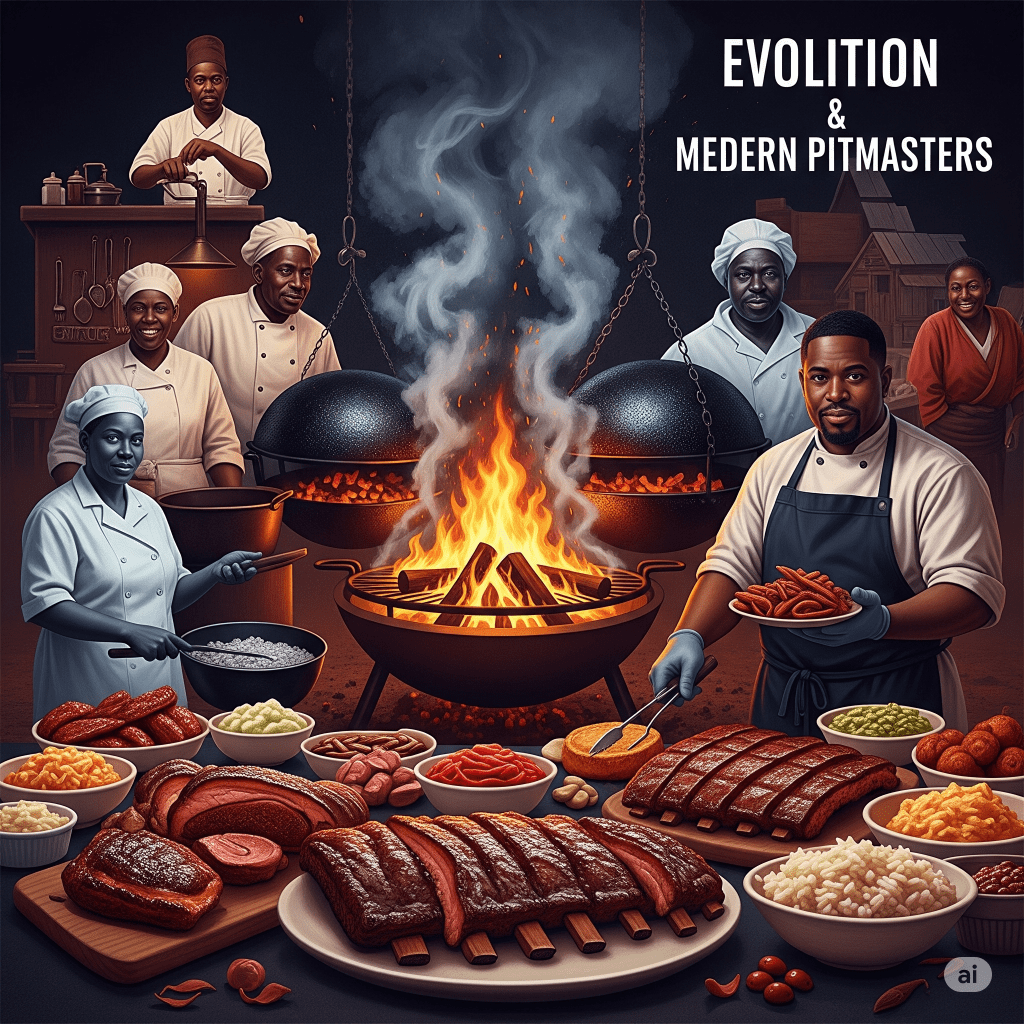

It’s no exaggeration to say barbecue as we know it wouldn’t exist without the skill, labor, and creativity of Black people in the South. Enslaved men — often the designated cooks during plantation “celebrations” (read: excuses to flaunt wealth) — became experts at slow-cooking whole hogs over pits, seasoning with regional spices, and developing what we now call “barbecue styles.”

They were chemists of flavor, DJs of smoke, chefs with no Michelin stars but all the culinary genius.

And yet? They weren’t just feeding the elite — they were feeding each other, feeding communities, and passing down traditions through resistance. Even after Emancipation, many Black cooks continued to make a living off barbecue, often feeding the same systems that tried to erase them.

BBQ Became America’s Favorite Dish — But at What Cost?

When white pitmasters and “BBQ competitions” started taking over the mainstream narrative, Black barbecue got sidelined — again. From commercial branding to televised competitions to food festivals, the spotlight often skipped the people who actually originated the craft.

And let’s not even start on the country clubs charging $45 for a “barbecue plate” while ignoring the fact that it was once literally cooked in shacks over open flames by people who didn’t even own their freedom.

Yet despite the whitewashing, Black barbecue legends kept thriving — names like Rodney Scott, Ed Mitchell, and B.J. Dennis began reclaiming the narrative and reminding the world where real pit mastery comes from.

So, Why Is It the Go-To Meal for the Fourth of July?

Simple. Because barbecue feels communal. It’s outdoors. It’s celebratory. It fills the air with nostalgia and smoke — a smell that, depending on who you ask, smells like joy, rebellion, or resilience.

But the deeper reason? It was always there. Even in the early days of American independence, enslaved people were cooking barbecue during parades and political rallies — because white folks demanded it. The Independence Day barbecue tradition wasn’t born in liberty — it was cooked in captivity.

Wild, right?

Let’s Get Real About What We’re Celebrating

There’s no shame in loving barbecue on the Fourth. In fact, if you’re lighting the grill this week, you’re keeping a long, complicated, powerful tradition alive. But while you’re at it, say a silent thank you to the hands who built it — the Black men and women whose seasoning blends and smoke skills turned scraps into masterpieces.

And maybe ask why their names don’t get carved into the side of food trucks or splashed across patriotic commercials.

Don’t Just Eat the Ribs. Honor the Roots.

Here’s how to bring the truth to the table this Fourth of July:

- Learn the names of Black pitmasters and regional styles beyond what’s trendy. (Memphis, Carolina, Kansas City? That’s all us.)

- Support Black-owned barbecue joints who are preserving the legacy without compromise.

- Talk to your kids, your partner, or your loud uncle about who really shaped American cuisine.

- Stop pretending barbecue sauce came from a bottle at the grocery store.

Final Take: Barbecue Isn’t Just Food — It’s a Cultural Archive

This July 4th, before you post that plate, recognize that barbecue carries the stories of stolen labor, of innovation under pressure, of love passed down through smoke signals. The flavor? That’s ancestral. The sauce? That’s resistance. The grill? That’s legacy.

You’re not just eating ribs. You’re eating history.

Leave a comment